Central Bank Digital Currency and the Dystopian World of Cashless Economy

With the rise of CBDCs, we are witnessing the birth of a new global monetary system - Here's what you need to know.

Assume that you and I are two random people from the Stone Age era that had begun roughly 2.6 million years ago. I require some stones and hunting tools from you in exchange for some meat that I possess. We both mutually and voluntarily decide to trade and exchange. This direct exchange of goods and services was the essence of the barter system that prevailed for a very long period. Human beings have been exchanging goods and services to achieve their end means for thousands of years.

However, the barter system had many flaws to be an efficient monetary system to facilitate trade. I mean, the barter system requires both parties to have the exact item the other person is willing to trade. What if I want hunting tools in exchange for some meat, but all you could offer is a cow. The failure of “Double coincidence of wants” forces everyone to wait until the perfect match of trade arrives on the market. Therefore, the barter system was a failure because it involved a wastage of time, efforts, and the absence of any standard unit that could efficiently facilitate trade. This is when people realized the importance of money as a medium of exchange.

Money is a tool that acts as an intermediary between the buyer and the seller. Instead of waiting for someone to exchange meat for hunting equipment, I would now rather exchange meat for money and use that money to buy hunting equipment. Any money can serve as a medium of exchange only when it is widely accepted as a method of payment in the markets for goods, labour, and financial capital. However, the medium of exchange is not sufficient but a necessary condition to make any commodity fit enough to qualify as “good money.” This is why your KFC vouchers, for instance, are not considered as money. The other important characteristics of “good” money are:

Store of Value: Money should maintain its purchasing power in the long term, rather than depreciate. But not every asset that is a good store of value qualifies for “good” money. For example, stocks, precious metals, real estate, bonds and other assets do preserve their purchasing power in the long term, but they do not qualify for other properties of money.

Unit of Account: It is the unit in which you denominate the prices of goods and services. It is the standard benchmark in which value is measured. For example, in India, prices of goods and services are denominated in Rupees.

Fungibility: Fungibility of money refers to the fact that all money is the same, interchangeable, and identical. The 10 rupees note in my wallet is the same as the 10 rupees note in your wallet. They are equally replaceable. Gold has been considered fungible (one gold ounce is equal to another gold ounce), for a long period of time, though in some cases it is not entirely true.

Divisibility: This feature of money indicates the fact that money must be easily divided into varying units.

Portability: Money should be easy enough to transfer from one place to another.

Durability: Any commodity that is fit enough to be ‘money’ must be strong enough to withstand being used repeatedly.

The main characteristics of money are summarized in the above infographic. Human history has had different forms of money since barter. In the early days, the indigenous tribe or certain community would use cowry shells, Rai stone, a specific bead, jewel etc. to facilitate transactions through social contracts. These commodity-based monies had value due to their utility, scarcity, wider acceptance by community or tribe, and aesthetic attractiveness by the whole community. Some economic anthropologists argue that Native American money took many forms besides shells such as furs, teeth etc.

Over time, precious metals such as Gold, Silver, and Copper became the foremost commodity-based forms of payment. Currencies based on precious metals had an intrinsic value as well as. a market value. That essentially means that Gold coins that you received as payment could be melted down to make something else, such as jewellery. Gradually, metal coins were introduced whereby precious metals were stamped into a regular size having a specific value.

The coinage era was followed by paper currency in the 1100s, when the Chinese Song Dynasty issued the world’s first government-backed paper money. This government-issued paper money was known as Jiaozi. Eventually, banknotes were introduced across the world and could easily be converted into gold or silver by the application at the bank. Over time, the world monetary system was mainly shaped by the various modifications of the commodity-backed currencies such as bimetallic standard, classical gold standard, gold exchange standard and the Bretton Woods System.

In 1971, the United States President Richard Nixon declared the “temporary” suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold that marked the end of the Bretton Woods monetary system. The “temporary suspension” of gold convertibility manifested into a permanent one, which has now resulted in a fiat monetary system.

Money in the Digital Era

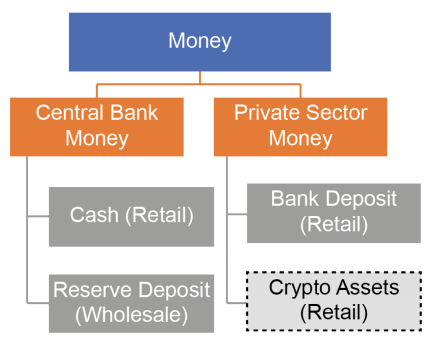

Today, most of the money we use is in the form of bills, coins, and its electronic equivalents, fiat currency. In a modern economy, the public uses two different types of money: Central bank money and commercial bank money. It is a gross misunderstanding that a central bank creates the nation’s currency, but in reality, most payments in a modern economy are made with private money issued by commercial banks in the form of bank deposits. These deposits can be accessed through credit cards, debit cards, loans, checks and other means of transferring money.

Economic anthropologists assert that money and its institutional foundations have always evolved in parallel with contemporary technologies and existing infrastructure. The rise of the internet in the last phase of the 20th century has paved the way for many instant and efficient innovations in the way we do our transactions and exchange goods and services. For example, Central banks around the world had rapidly adopted a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system for transferring instant funds from one bank to another or one major financial institution to the other. In 1985, only three central banks had implemented the RTGS system, but in the next 20 years, the majority of central banks had introduced the RTGS systems for large-value interbank funds transfers.

Fast Payment Services (FPS) are those services that process transactions in which the transmission of the payment message and the availability of final funds to the payee occur in real-time or near-real-time or as near to a 24-hour and seven-day (24/7) basis as possible. According to the World Bank’s 2020 report titled, “Fast Payment Services”, an increasing number of countries have an FPS in place and several others have announced their plans to go live. The adoption of FPS as a means to allow instant settlement of payments between households and businesses has been remarkable in the last 15 years. Examples of FPS are:

Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in India

PIX in Brazil

Target Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) in the euro area

CoDi in Mexico

The developments in the last 25 years have proven that innovation in the settlement of payments and technological advancements in monetary infrastructure can enhance the consumer experience, financial inclusiveness, and instant transfer of funds. However, they do have various shortcomings and haven’t really achieved their objectives. Nevertheless, the innovation in retail payments and the digitalization of our money are booming both in the private and public sectors.

Declining Use of Cash

We still use cash, and it is still a widely accepted payment system in the world. Its popularity lies in the fact that it is a simple, easy, robust payment mechanism that requires no ancillary technologies. It is an excellent tool to settle transactions by simply exchanging the currency as it doesn’t require any magnetic-stripe card, internet connection or mobile device. A seller of goods and services does not need to have a card-reading machine or any payment receiving device to settle transactions. As we can see from the following infographic, Cash is still a dominant mode of making payments.

Advocates of maintaining cash as a dominant method of payment assert that a significant reduction in usage of cash would further marginalize people and limit their access to the existing financial system, make them vulnerable to frequent cyberattacks and invade people’s personal and transactional privacy.

However, with the rise of innovation in payment technology and digitization of money, retail consumers have begun to explore alternative means of payment beyond cash. Digital wallets have become the preferred medium for online shopping, long-distance transfer of funds and accepting donations from social media users.

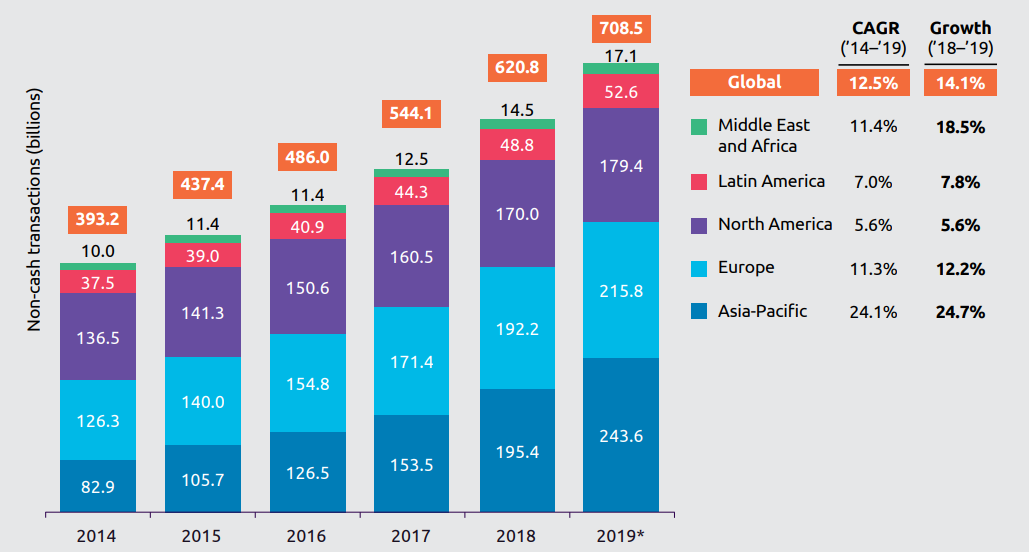

Yes, the ratio of physical currency in circulation to GDP is pretty stable in the last decade, but the volumes of non-cash transactions have been on the enormous rise. According to World Payment Report 2020 by Capgemini Research Institute, global non-cash transaction volumes grew 14% (2018-19) to reach 708.5 billion — the highest surge in the last decade.

Interestingly, this growth is not driven by the developed nations of the West, but rather by developing countries of Asia and Africa. It can be observed from the above figure that the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of non-cash transactions was 24.1% in the Asia-Pacific region and 11.4% in the Middle East and Africa. This surge is driven by increasing penetration of smartphones, a booming e-commerce sector, growing adoption of digital wallets, soaring internet economy and innovation in mobile or QR code payments.

COVID-19 has played a major role in accelerating people’s familiarisation with non-cash or digital transactions. In February 2020, the Chinese banks had started disinfecting and isolating used banknotes with the help of ultraviolet light or high temperatures in order to stop the spread of coronavirus. Subsequently, in March 2020, the World Health Organization had warned against using cash amid fears it could be spreading coronavirus, although, they later denied this claim stating that they were “misrepresented.”

The Bank for International Settlements, which advises central banks around the world, released a bulletin in April 2020 stating that the pandemic could drive society’s shift towards non-cash alternatives. In the bulletin, the BIS also highlighted how the google search for relevant terms like ‘Cash Virus’, ‘Cash Covid’, “Cash Corona” skyrocketed after these headlines induced a feeling of fear.

The Mastercard New Payment Index has concluded in their research that 93% of people will consider using at least one emerging payment method, such as cryptocurrency, biometrics, contactless, or QR code, in the coming years. As they describe:

Nearly two-thirds of respondents (63%) agree they have tried a new payment method they would not have tried under normal circumstances, but the pandemic has galvanized people to try flexible new payment options to get what they want, when they want it.

The Rise of Blockchain-Based Digital Assets

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum have taken the world by storm in the last few years. There has been an impressive growth in the value and number of cryptocurrencies in the market. Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency was launched in January 2009 as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system that would allow “online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.” Today, there are over 11000+ cryptocurrencies with a market capitalization of 1.85 trillion dollars and this phenomenal adoption would continue to grow as the large capital of traditional corporations, venture capitalists, hedge funds, high net worth individuals, asset managers and even retail investors continue to pour in.

However, cryptocurrency is not the only digital asset in the blockchain ecosystem. A whole class of innovative digital assets built on blockchain are emerging which has been drawing retail and institutional investors’ attention. Examples of emerging digital assets are decentralized protocols/platforms, utility tokens, Non Fungible Tokens and asset-backed tokens.

Bitcoin’s extreme price volatility is one of the reasons why many people claim Bitcoin is incapable to become a suitable currency to facilitate daily transactions. And they are kind of right, Bitcoin has a very volatile price history. For example, in August 2012, Bitcoin had lost nearly 56% of its value in the span of three days. Subsequently, in April 2013, Bitcoin’s price declined by over 83%. The advocates of Bitcoin do not deny this fact but they argue that price volatility is an inherent part of its growth, not the consequence, as upward volatility (which is associated with descending volatility) would help to grow its market cap, network effects and achieve a state of price equilibrium in the longer term.

Anyway, for now, cryptocurrencies, in general, have extreme price volatility and to tackle this price volatility, a new model of cryptocurrencies called Stablecoins were developed. Stablecoins are digital currencies that are pegged to real-world assets such as fiat currencies like dollar or gold in order to maintain a stable value. They have been gaining a lot of popularity as they are cryptographically secure, low-cost and most importantly, price stable. Some of the popular stablecoins are Tether, USD Coin, and Dai.

In the last couple of years, various private entities have launched (or are in the process) their own versions of cryptocurrencies or tokens for specific purposes. For example, JP Morgan Chase became the first global bank in 2019 to design a network to facilitate instantaneous payments using blockchain technology. Their token was known as JPM Coin and it is primarily designed to enable the instantaneous transfer of value between JP Morgan clients that hold accounts in the bank.

In 2019, Facebook had announced that they are working on their own cryptocurrency project known as Libra (presently known as Diem) and revealed the structure of the project in detail. According to Diem’s white paper, Diem would work as a single currency stablecoin that would be backed 1:1 by the Reserve, which will consist of cash or cash equivalents and very short-term government securities denominated in the relevant currency.

The goal of the Libra would be to serve as a foundation for financial services, including a new global payment system that meets the daily financial needs of billions of people by assuring high transaction throughput, low latency, flexibility and an efficient, high-capacity storage system. Facebook’s plan to launch its own cryptocurrency which could potentially be adopted by billions of people was met with strong opposition from governments, banks and financial regulators. They have repeatedly asserted that they would ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations. The ongoing developments seem positive but let’s see how they will function in a very highly competitive market.

Central Bank Digital Currency

We have discussed so many rapid advancements in digital payments and monetary infrastructure that are materializing in the current world scenario. Disruptive technological innovations have always challenged the existence of the status quo framework. And with the declining use of cash, expeditious rise of cryptocurrencies, rapid integration of blockchain and instant global payment technologies — it is posing an existential threat to central’s banks’ monopoly on money, monetary architecture and means of settlement of payments.

Perhaps, the most significant recent development is the entry of big corporations like Facebook, JP Morgan and other players who are planning to enter into this dynamic sector. Take Facebook, for instance, its business model is based on direct interaction with its 2.6 billion users and their data that are an essential by-product of these interactions. As big techs like Facebook enter into digital payment and start issuing their own native currencies, these factors give them a strong competitive advantage triggered by strong network effects — possibly leading to centralization of power and decision making.

With so many developments unfolding in the private sector about how we define our money, settle our transactions and decide our monetary policy - the central banks around the world have started reacting and taking significant efforts to position themselves at the centre in this changing landscape. This is why they are coming up with their own digitally issued currency known as Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

A central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a new form of money, issued digitally by the central bank and intended to serve as legal tender. It can also be observed as a digital form of the traditional fiat currency and could be exchangeable one-to-one with the fiat currency. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) which serves as a bank for all central banks around the world define CBDC as a digital payment instrument, denominated in the national unit of account, that is a direct liability of the central bank. It would be a sovereign currency in electronic form.

CBDCs might seem confusing because most fiat currencies such as dollars, pound, yen, rupee, euro and so on already exist in electronic form. For example, India’s total money supply (M3) stands at Rs. 19372035 crore as of July 30th 2021 but only Rs. 2839354 crore takes the form of physical cash. The rest is simply numbers on electronic balance sheets of the commercial banks and mostly takes the form of bank deposits. Confused? Let me simplify it for you.

In the current monetary system, central banks issue two different types of money and provide infrastructure for the third one. The two types are:

Physical cash (i.e. banknotes and coins). These are widely accessible and peer-to-peer. They do not have any intrinsic value in the modern economy and they are not redeemable.

Bank reserves. These are electronic and accessible to only selected qualified financial institutions (mainly commercial banks). These reserves can be understood as current account balances held by commercial banks at the central bank in the same way that individuals hold such accounts at commercial banks.

Thus, central bank money is comprised of cash and reserve deposits and from an accounting perspective, both act as a liability of the central bank. However, most money in the modern economy is issued by the commercial banks through demand deposits that people have at commercial banks. These bank deposits can be accessed with checks, debit cards, credit cards, or other means of transferring money. Our bank deposits at commercial banks are not legal tender but their values are denominated in legal tender and can easily be exchanged at a one-to-one value. Money is also created out of thin air when a bank makes a loan. What does it mean? Let’s understand with the help of an example.

Suppose you want to buy an expensive car and to finance it, you take a loan from a commercial bank. The bank does not typically give this “loan” to you by giving thousands of rupees worth of banknotes. Instead, it credits your bank account with a bank deposit of the size of the loan. And at this moment, new money is created. It is widely assumed that banks make loans when they have enough deposits to lend them out but in reality, they don’t need to wait for any deposits instead, loans create deposits and the new money is created. Yep, out of thin air.

If you want to read more on this topic, you can read the Bank of England’s paper titled, “Money Creation in the Modern Economy” to understand the money creation by the commercial banks in the present times.

Therefore, commercial banks are the major entities that facilitate money creation in the modern economy and distribute money to the general public for various uses such as paying rents, buying goods and services etc. Central banks influence commercial banks’ money creation activities through their monetary policies such as by lowering/raising market interest rates by purchasing/selling government securities in the open market and hence central banks are indirectly linked to the general public.

The whole issuance of the central bank money and private money in the modern society through the central bank and commercial bank channels could be summarized as:

The bank deposits which we have discussed previously are the liabilities on the commercial banks’ balance sheets but with the introduction of CBDC, this liability would be held by the central bank — making it the third form of liability for the central bank, alongside cash and central bank reserves.

The general purpose of the CBDC is to introduce a completely new form of central bank money to provide and distribute it conveniently to the public. With CBDC, central banks aim to provide safe, instant, liquid payment instruments “directly” to the general public — similar to what central banks have been doing for financial institutions using reserve deposits till now. Central banks claim that this would accelerate the rate of financial inclusiveness.

Different Types of CBDC

CBDCs are often compared with decentralized digital currencies such as Bitcoin that are secured by public-key cryptography. While the underlying technology might be similar but they differ widely in their fundamental properties and objectives.

For example, most cryptocurrencies are decentralized while CBDCs are centralized in nature. Cryptocurrencies offer you pseudonymity while CBDCs would allow central banks and governments to know exactly who holds what. Central banks do not have a positive approach and they have reiterated their pessimistic views on bitcoin often. And this is evident from the recent speech delivered by T Rabi Sankar, Deputy Governor of Reserve Bank of India.

Private virtual currencies sit at substantial odds to the historical concept of money. They are not commodities or claims on commodities as they have no intrinsic value; some claims that they are akin to gold clearly seem opportunistic. Usually, certainly for the most popular ones now, they do not represent any person’s debt or liabilities. There is no ISSUER. They are not money (certainly not CURRENCY) as the word has come to be understood historically.

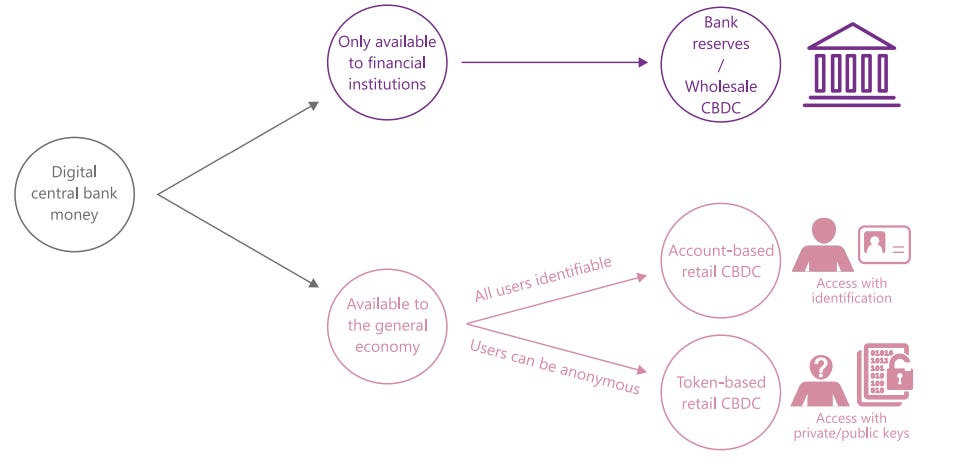

The design and institutional framework for the CBDCs may vary from country to country. However, CBDCs are classified into two different types depending on the target user base. The two types are:

Retail Central Bank Digital Currency

Wholesale Central Bank Digital Currency

Retail CBDC is the one that will be issued to the general public. In the traditional two-tier monetary system, the central bank money is inaccessible to the public but with the help of Retail CBDCs, central banks plan to make central bank digital money directly accessible to the general public — similar to how cash is now available to the general public as a direct claim on the central bank.

Retail CBDCs do not any involve any credit risk as they are the direct claim on the central bank. It would mostly be based on Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) that include features such as traceability and availability. With the help of retail CBDC, central banks in the emerging economies wish to reduce the cost of printing and managing cash and contain the associated crimes by promoting cashless payment tools.

Retail CBDC proposals are popular among emerging economies, mainly because Retail CBDCs could speed up financial inclusion and might promote digitization of the economy. Emerging economies are eager to develop global financial centres in their cities and view advancements in the fintech sector as one of the most convenient ways for accomplishing this objective.

A Wholesale Central Bank Digital Currency is for financial institutions that hold reserve deposits with a central bank. Wholesale CBDCs are intended to improve the efficiency of the settlement of interbank transfers and other wholesale transactions such as settling payments between financial institutions.

They may also simplify cross-border payment infrastructure — strongly reducing the number of intermediaries involved. It may perhaps significantly reduce counterparty credit and liquidity risks

While there are so many design proposals for the retail CBDCs, two of these are most popular. These are:

Token-based Central Bank Digital Currency

Account-based Central Bank Digital Currency

Tokens are not a new thing and have existed way before blockchain or cryptocurrencies came into existence. Conventionally, a token is an object that represents something else such as another object (physical or virtual) or it can even represent any form of economic value. Crypto tokens are a type of cryptocurrency that represents an asset that resides on a blockchain. Crypto tokens are used for investment purposes or as a currency on a specific blockchain.

In a token-based CBDC framework, CBDC would be issued as a token with a specific denomination. Token-based CBDC would ensure transactions between two people would be initiated by digital signatures and secured by public-key cryptography. Users need to remember their password-like private key or they could lose access to their funds. Such a system would not require users’ personal identification data — thus ensuring a significant level of transactional privacy or anonymity.

Another approach to CBDC is based on the account-based framework that would rely on verifying the user’s identity to confirm the ownership of funds. This type of system resembles the digital payment systems that we use today. All transactions can be associated with your real-life identity and to initiate a transaction, users need to confirm their identity as it happens today through passcode or OTP.

I favour token-based CBDCs over account-based ones because it would ensure wider and less complex accessibility and be able to ensure a better level of transactional privacy - just like cash. However, it may perhaps lead to severe issues with regard to private key management by the retail users. If you forget the private keys of your wallet then you might no longer have access to your funds.

Central banks favour account-based CBDCs because they are more compatible with the monitoring of criminal activity and would be easier to regulate. The Bank for International Settlement’s report claims that they would design the CBDC framework in such a way that would preserve people’s privacy, but I highly doubt the authenticity of their claims. As we will see later in the section, these issues are linked to broader policy debates associated with data governance, payment surveillance and privacy.

The various forms of CBDCs that we have discussed so far are summarized in this picture.

Tracking CBDC Development

CBDC development by the central banks and major financial institutions have accelerated over the past few years and the reasons are clear — the rise of stablecoins, the popularity of cryptocurrencies, declining use of cash, increasing use of digital payment services and the interest of large corporations like Facebook to launch their own currencies.

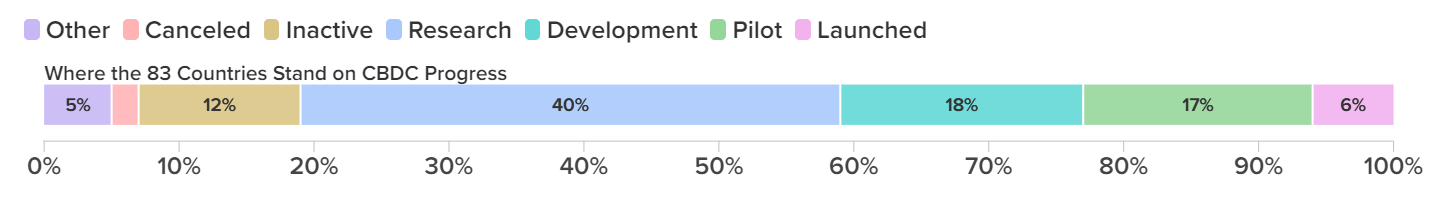

According to the Atlantic Council’s CBDC tracker, central banks of 81 countries (representing over 90% of global GDP) are actively working on the development of their own Central Bank Digital Currency, with more than 10 countries are in the pilot experimentation phase and preparing a possible full launch. In May 2020, only 35 countries were exploring CBDCs and this trend will keep on progressing as central banks will continue to investigate CBDC feasibility without committing to issuance.

The US dollar is not only the currency of the United States but it also enjoys the privilege of being the world’s reserve currency. And the institution that controls, regulates and promotes the US dollar has shown its interest in the CBDC. The Federal Reserve see stablecoins and cryptocurrencies as a threat to the existing financial system and they anticipate CBDC would be the perfect counterbalancing response to it. This is evident from Fed chair Jerome Powell’s recent speech:

For the past several years, the Federal Reserve has been exploring the potential benefits and risks of CBDCs from a variety of angles, including through technological research and experimentation.

In February 2021, he provided testimony at the US Senate Banking Committee, where he acknowledged the deployment of a digital dollar is a “high-priority” project for the Federal Reserve.

In the Euro area, the European Central bank issues money for the general public. Due to technological advancements, European Central Bank (ECB) has been proactively working to make sure people’s transition into cashless payment is as safe, smooth, and effective as possible and thus they are issuing their own CBDC - the digital Euro. It would essentially be an electronic version of banknotes and coins that would be operational in the Eurozone.

The digital Euro will likely be a digital wallet that citizens can keep at the ECB and it gives its holders a claim against the ECB — similar to banknotes and coins, but in digital format. On 14th July 2021, the European Central Bank had launched the investigation phase of the digital euro project that would analyze how a digital euro could be designed and distributed to everyone in the euro area.

The investigation phase will examine the use cases that a digital euro should provide as a matter of priority to meet its objectives: a riskless, accessible, and efficient form of digital central bank money. Their experimental work has concluded that the existing infrastructure for instant payments coupled with distributed ledger technology could be used to scaled up to process the roughly 300 billion retail transactions carried out in the euro area each year.

Central banks of many countries are striving to understand how CBDCs could challenge the existence of traditional forms of money and carefully examining how they could design it for their best advantage. As a result of which a huge volume of literature, reports and proof of concept (POC) have emerged around CBDCs. This is clearly evident from Atlantic Council’s CBDC development tracker — out of 83 countries, 32 countries stand on the research stage, 16 on the development stage, 14 countries on the pilot stage, and 5 countries have deployed the CBDC so far.

Let’s review some important countries and scrutinize their efforts to develop CBDCs.

China

Among all CBDC initiatives around the world, China’s efforts to launch CBDC appears to be the most developed and closest on the largest scale. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has been working on the digital yuan or e-CNY since 2014, where it had set up a task force to study digital fiat currency. In 2016, the PBoC established its Digital Currency Institute, which developed the first-generation prototype of digital fiat currency.

In 2017, PBoC started the e-CNY project where it had selected large commercial banks, telecom operators and Internet companies with high rankings to design, develop and improve e-CNY apps. In 2020, China became the first major country to pilot test the CBDCs, starting with 4 cities — Shenzhen, Suzhou, Xiong’an, Chengdu. “The pilot runs were designed to test the reliability of theories, the stability of systems, the usability of functions, the convenience of processes, the applicability of scenarios and the controllability of risks”, PBoC notes.

More public tests were conducted in Shanghai, Hainan, Changsha, Xi’an, Qingdao and Dalian from November 2020. Li Bo, deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China has said that they will likely test their e-CNY on international athletes and visitors during the upcoming Beijing Winter Olympics 2022. Furthermore, China actively encourages free giveaways of their CBDCs to incentivize people and to speed up the adoption of their digital currency.

Sweden

The Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden aims to implement its own retail central bank digital currency which is known as e-krona. They have started working on the e-krona project in 2017 in order to investigate what role the Riksbank could play in an increasingly digitalized world. Since then, it has issued several reports and research papers to study the economic implications.

The International Monetary Fund remarks that Sweden’s e-krona project is more advanced than similar projects in other developed countries. The underlying technology to support the e-krona infrastructure is built on R3’s Corda system. In February 2020, the Riksbank signed an agreement with the consulting firm Accenture for its role as a supplier of the technical solution required for the e-krona pilot and to test e-wallets, distributed ledger technology and interoperability with banks.

E-krona’s first pilot phase was tested from February 2020 to February 2021 with the purpose of the pilot being to increase the knowledge of central bank-issued digital krona. Upon its completion, they extended the CBDC pilot for a further 12 months, taking it to February 2022. In April 2021, they released a report based on the analysis of the first pilot phase and concluded that token-based e-kronor can be used for transactions in accordance with the distribution model. The Riksbank is also investigating if they can offer offline payments via e-krona.

Eastern Caribbean

The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) is the central bank for the USD pegged Eastern Caribbean dollar and monetary authority for a group of eight island economies — Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines. The islands have a combined population of around 620,000 people, assisted by only 21 licensed commercial banks and physical detachment from conventional financial infrastructure provides a viable environment for issuing their own CBDC to offset the difficulties of printing, distributing and managing cash.

Therefore, the ECCB has been diligently working on their CBDC deployment. The motivating factors for their digital currency deployment are payment efficiencies, financial inclusion, reduce cash usage within the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) by 50% and promote economic development led by fintech innovation. The ECCU’s CBDC is known as DCash. It is simply the digital version of their Eastern Caribbean dollar. It aims to offer a safer, faster, cheaper way to pay for goods and services and send EC funds to other Dcash users.

After conducting a CBDC pilot with a partnership with Barbados-based fintech company, Bitt in 2019 and 2020, the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank has now officially announced that DCash would be operational as CBDC within the formal currency union. It became the world’s first retail central bank digital currency to be publicly issued and to consider as a legal tender, under currently enacted legislation.

This is a remarkable move as it would demonstrate the functionality and effectiveness of a centrally backed digital currency in smaller or island-based economies. If successful, it could encourage developing countries to design and speed up their process of CBDC development as they share the same objectives — promote financial inclusion, payment efficiency and economic growth via fintech innovation.

Multiple CBDC (mCBDC) Bridge

Cross border fund transfers are essential for economies in our increasingly globalized world and it underpins sectors such as tourism, remittances and e-commerce yet they remain slow, inefficient and expensive. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) observes that integration of Central Bank Digital Currencies of many countries, forming multi-CBDC (mCBDC) arrangements could greatly enhance cross border payment inefficiency.

Today, cross border payments involve multi-currency conversions before the final settlement of funds. This is a complex process as you have to deal with several intermediary parties, higher cost of compliance and limited transparency on the status of payments — creating frictions between cross border banking arrangements. With the help of the mCBDC framework, interoperability between payment systems involving cross-border and multiple currencies could increase considerably. The research on the broad outline of such a system is still in its infancy.

An example of such a project is the mCBDC Bridge which is an ongoing co-creation project of central banks of 4 countries - Hong Kong, Thailand, United Arab Emirates and China. It aims to develop a working prototype to support instant cross-border payments in multiple currencies among multiple jurisdictions. The group of central banks are also exploring the aspects of scalability, data governance, privacy and efficient interoperability.

It is worth highlighting that the interest of retail-based CBDCs is more popular in developing countries than in developed countries. The reason could be that the major proportion of the population is banked in developed countries and thus, financial inclusion is not an urgent issue for them. Anyway, these are just a few of the many developments happening in the CBDC landscape and I hope the different projects we have discussed so far were able to give you an idea of how our future currencies would look like, digital and centralized.

The Dystopia of Cashless Economy

After exploring so many topics in this article so far and we can conveniently conclude that we are heading towards a cashless society triggered by the declining use of physical cash, the rise of cryptocurrencies, credit and debit cards, fast payment services, and ultimately, the accelerated investigation of CBDCs by the central banks around the world. This is evident not only from the decreasing cash-to-GDP ratio but also from the increasing share of digital payments in the total transactions.

I mean, you could introspect for yourself about how transactions have already been digitalized in our personal lives in the last few years. The rich and upper-middle-class barely use cash as a mode of payment these days — from ordering a book on Amazon to buying your favourite tasty Domino’s pizza, the digital means of payment have already been integrated into our daily lives. And it’s not about rich or middle-class people alone, digital means of payment have started gaining adoption among the poor and in rural parts of the developing world.

I am not even “speculating” or making up the narrative of the cashless society. Many countries have already shown their interest and are on the verge to become cashless economies in the imminent future. Sweden’s cashless experiment would be the best case study for this purpose. Sweden has always been at the forefront in embracing new technologies and innovations, especially when it comes to finance and currency. In 1661, it became the first country in Europe to introduce banknotes when Stockholms Banco became the first bank to issue banknotes.

Fast forward to the 21st century, the country now looks forward to becoming the first country in the world to fully go cashless by 2023. Sweden’s thriving fintech sector, government support and societal perception towards cash are driving factors for the transition. The percentage of people using cash as a medium for settling transactions have decreased significantly over the last 10 years — from almost 40% in 2010 to a mere 9% in 2020. As the Swedish government and banks are actively encouraging people to integrate into their cashless society, it is expected to see a further drop in cash usage in Sweden.

The Riksbank, the Swedish Central Bank’s working paper titled “Withering Cash: Is Sweden ahead of the curve or just special?” noted that Sweden and Norway are the only countries in which the volume of cash in circulation have declined heavily from 2009 to 2019. Nominal cash volume decreased by 43% in Sweden in the last ten years. This is significantly huge. Apart from small businesses, and small transactions, the businesses, banks and government are actively discouraging the use of cash in daily transactions. For example, many public transport facilities in Stockholm have stopped using cash as a reliable means of payment. Tickets are either pre-paid or can be purchased using credit/debit cards at ticket vending machines or via the SL app.

Of course, the transition towards a cashless society wouldn’t occur overnight. But with the rise of digital means of payment, the popularity of mobile payment applications like Swish, discouraging cash payments at shops and the introduction of e-krona, it wouldn’t be that astonishing if Sweden transforms into a fully cashless society by 2023. Sweden isn’t the only country in the cashless society race — countries like Finland, South Korea, China, and Australia are likely to follow Sweden in this decade.

Indeed, it is imperative to ask that what’s wrong with going fully cashless or digital? Wouldn’t it improve our payment efficiency and save time? Wouldn’t it save our transactions costs because there are fewer intermediaries? Wouldn’t it speed up the financial inclusion of emerging economies? Governments around the world would also be able to monitor illicit activities and money laundering — so what’s wrong? Well, every technology has its own flaws but in the case of CBDCs, the flaws are dystopian in nature. Let’s discuss some of its flaws:

Jeopardizing people’s transactional privacy

Fueling the Surveillance Capitalism

Serious consequences of negative interest rates

There is no “one size fit all” CBDC model and the structure of the CBDCs would differ from country to country depending on the prevailing legal, political, social and economic challenges of the region that it aims to solves. However, one thing is certain, the central banks would design their digital currencies in such a manner where they would have the capacity to track every transaction of every user. People need to '“trust” centralized entities to protect their privacy.

The ability of central banks and corporations to monitor every transaction would ultimately threaten people’s transactional privacy, liberties and freedom. Many people would completely be oblivious to their transactions being monitored by centralized entities. Central banks would likely collaborate with third-party financial institutions to deploy their digital currencies which would give corporations easy access to the intimate details of everyone’s financial life.

When it comes to privacy, CBDCs are in complete contrast with traditional cash as the cash transactions are peer-to-peer, permissionless and censorship-resistant. Cash transactions do not require any intermediary agents to guarantee transfer of value — you simply transfer ownership of your cash by simply exchanging it with other people. Cash is more private than cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin since the government have sufficient tools to make your bitcoin address traceable to your real-world identity.

However, in a cashless society, all transactions will be intermediated and you need to rely on intermediary institutions, be it government or banks or other financial institutions in order to assure transfer of value from one person to person. It simply means transactions in a cashless society would not be peer-to-peer, censorship-resistant and permissionless, as you need authorization from intermediary institutions to transfer money.

In a cashless society, the intermediary institutions should essentially have to record personal details of their users, transaction amount, time, location and the counterparty involved in order to record accurate ledger entries. The personal transactional data coupled with social media activities of the people would create such a dystopian system where a bunch of corporations and government would have total control and power to surveil what you buy, to whom you send money, where you live, what your political inclinations are (based on your social media activities, browsing history etc.) and so on — essentially creating a global surveillance economy.

According to the 2020 Human Rights Foundation’s (HRF) annual report, around 4.2 billion people live in some form of an authoritarian country. The people under these oppressive regimes already have little tools at their disposal in order to resist, protest and peacefully raise voices against socio-economic issues such as inflation, corruption, ethnic cleansing, inequalities, lack of basic facilities, and crimes.

CBDCs would be an additional tool in the hands of fascists to clamp down on critics and suppress the socio-political movement of oppressed people by having the ability to deny their participation in the financial system. It would also enable them to track identities and monitor the activities of the people associated with political dissenters.

Federal laws of many developed nations that are aimed at curbing criminal activities are designed in such a way that makes funds sent to specific “high-risk” countries vigilant in nature. There have been many incidences in the past, where humanitarian organizations faced difficulties to transfer funds to vulnerable communities in oppressive or war-torn regimes. As one Wall Street Journal article notes:

U.S. and European banks have shut the accounts of a number of U.S. charities and have held up money transfers by others, hindering their ability to deliver aid to refugees and others in Syria, Turkey and Lebanon. Because both charities and banks are reluctant to discuss the issue, it isn’t possible to know precisely how widespread the problem has become.

The problem is exacerbated by multiple checkpoints installed by the authoritarian regimes to make funds inaccessible and expensive to aid workers. The issues regarding funding delays and other banking-related problems have severely affected many American human rights groups and in some cases, have led to the closure of their bank accounts. As CBDCs would accelerate financial surveillance, the aid organizations might face even more difficulties to fund and support vulnerable communities in oppressive regimes.

In the worst-case scenario, the governments could literally exclude individuals, aid organisations, or the entire community from participating in the financial system. This would leave them with little to no alternatives. In the last decade, accounts of many organizations like Wikileaks, and Sci-Hub were frozen by Paypal, and the likes of Visa and Mastercard refused to process donations, as they were under political pressure to do so. In the end, they were left with fewer options and turned to Bitcoin donations to support their portals.

Therefore, in autocratic regimes or in pseudo-democratic countries like India, political dissidents, minorities belonging to marginalized castes, religion, sexuality, gender or ethnic minorities could easily be targeted by simply revoking their access to central bank digital currency — conveniently leading to their financial exclusion.

China’s highly digitalized economy governed by the authoritarian CCP government illustrates the dangers of a cashless society. Cash-based transactions are already been declining in the country as the majority of the population use online payment platforms such as WeChat Pay and AliPay as their first choice for settling transactions. Over the years, they have dominated this sector having a combined market share of over 90%.

These two companies have unprecedented visibility into user’s transactional data. This payment data when linked to people’s real-world identities have allowed them to engineer a far-reaching social credit system that monitors consumer’s trustworthiness and creditworthiness by examining their financial history. This is not just limited to surveilling your payment behaviour but also social media behaviour to determine whether the user’s social behaviour is “healthy.”

A consumer with a high social credit score will be awarded certain privileges such as - easier access to credit and loans, priority in school admissions and employment, permission to travel abroad, cheaper public transport, shorter wait times at hospitals and so on. A low social credit score can lead to punishments such as exclusion from booking flights or train tickets, slower internet speeds, and restricted access to various public/private services. Yes, the current social credit system is voluntary and operated mainly by private/local government bodies, however, China aims to introduce a nationwide social credit system in the imminent future - this is clearly evident from their recent national level notices and reports attempting to examine the possible structure for nationwide social credit system.

E-CNY, China’ CBDC project would make it easier for the Chinese government to rapidly expand its social credit system for its citizens and has every incentive to make it mandatory in order to monitor, surveil and algorithmically regulate the financial, social, moral and political behaviour of its citizens. Sure, the governments would demonstrate how such dystopian systems can make our life convenient and assure their citizens on “protecting” their privacy, however, in the end, everything boils down to the “trust” that we have to place in authoritarian governments and corporations.

This kind of social control and excessive concentration of power is made possible when ordinary citizens living in cashless societies do not have access to peer-to-peer, permissionless and censorship-resistant currencies and are left with no choice but to use intermediary forms of money that violates people’s privacy. Ultimately, such dystopian societies enabled by the Orwellian hunger for power would disproportionately affect vulnerable and marginalized communities around the world.

Negative Interest Rates

Another reason why central banks are looking to add another tool at their disposal is that it would, in theory, improve the effectiveness and transmission of monetary policy by more direct implementation of policies to achieve the desired objectives such as output stability, price stability, or to stimulate the economy through consumption and investment by adjusting macroeconomic factors. However, central banks are more interested in increasing the effectiveness of negative interest rates across the whole economy by issuing interest-bearing CBDCs.

Under a negative interest rate policy (NIRP), you are required to pay periodically to keep your money with the bank — instead of receiving money on your bank deposits. Financial institutions such as commercial banks are also obliged to pay interest to central banks for parking excess reserves with the central bank. The reason being, it discourages commercial banks and individuals from holding on to cash. It incentivizes banks to lend more money, and individuals to invest and spend money in order to boost economic growth.

The negative interest rate policy has always been an unconventional monetary policy tool, mostly restricted to economic textbooks. But in recent years, especially after the 2008 global financial crisis, many developed countries have resorted to NIRP as they have been stuck with low growth and low levels of investment and inflation. Central banks of Denmark, the Euro area, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland have turned to negative interest policies for a long time now. Switzerland ran a de facto negative interest regime in the 1970s to counter the Swiss franc’s appreciation, while the central bank of Sweden was the first to officially introduce negative interest rates in 2009.

Today, the extent to which the central banks could lower their nominal interest rates is constrained by zero-lower bound (ZLB). It is because physical cash is still widely available, serves as a store of value and has a nominal return of zero. I mean if a bank charges you a negative interest rate, instead of paying the bank to keep your money, you would simply liquidate your deposits and shift to cash. Therefore, the negative interest rate policy of central banks has not been really effective to stimulate economic growth as they had previously anticipated. However, CBDCs could change that.

The effectiveness of NIRP could be improved if the currency itself carries a negative interest rate. The gradual decline of cash coupled with the widespread introduction of CBDCs would be an easier approach to accomplish that goal. In the extreme case, the holders of CBDC would automatically pay a fraction of their CBDC amount and the money in their digital wallets would gradually decline. This would incentivize people to purchase goods and services — possibly fuelling consumerism.

The adverse implications of negative interest rates could only be realized if the cash substantially disappears from society, and by forcing people to use central banks’ interest-bearing CBDCs. Many central banks could possibly design their digital currencies on the same lines, clearly evident from their papers. For example, the ECB’s blog states that that the ECB is planning to “impose significantly more negative interest rates” via a digital euro. In ‘The Curse of Cash”, widely acclaimed economist Kenneth Rogoff strongly argues for gradual “phasing out” of cash and the development of negative interest rates policies.

Negative interest rates could have a disastrous effect on our financial and banking systems. People might not be willing to hold currency authorized by the government if it discourages savings and disturbs their intertemporal allocation of resources. Sure, the government might persuade people that a limited amount of CBDCs would not carry negative interest rates, however, when the central banks, distinguished economists, IMF, financial media and academia are gradually but aggressively pushing for interest-bearing CBDCs and phasing out of physical cash — I don’t see any optimistic future ahead.

Conclusion

In this long essay, we have extensively discussed the whole idea of money, its ideal properties and the evolution of money from barter to a multitude of digital payment technologies such as RTGS, FPS, cryptocurrencies, digital currencies of corporations and so on. The rapid popularity of Bitcoin, stablecoins and other cryptocurrencies have prompted central banks to develop their central bank digital currencies. And as we have seen, the understanding and pilot experimentation of CBDCs have advanced significantly over the past few years.

CBDCs could offer numerous benefits in monetary policy and payment efficiency but they come up with considerable costs. As we have described in this essay, how CBDC, an intermediary form of money could act as a dystopian tool for governments and corporations to monitor the financial activities of individuals that have serious social, political and economic consequences. In a truly democratic society, individuals should have the freedom and liberty to criticize their governments, protest for their fundamental rights, and engage in critical thinking. But when your actions are being monitored by governments and corporations, they are able to control your social, economic and political behaviour.

Privacy is our fundamental right and notably, it underpins other human rights. The invasion of privacy has always led to the persecution of political dissidents, ethnic minorities and innocent civilians and human history, if anything, proves that we cannot simply rely on governments and corporations to protect our privacy. We need to come together and fight for our fundamental right to privacy. The least, I would expect from people is to hold their governments accountable and ask for a reasonable level of privacy and anonymity in central bank digital currencies.

I am an independent researcher, and I try my best to keep my articles simple enough to comprehend even for people who do not have a background in economics and cryptocurrencies. If you like my work, please consider donating a little to keep my blog functional. Thank you!

You can send me your contributions via following portals:

Paypal: https://www.paypal.me/shreyas020

Bitcoin (BTC) Address: bc1qy4r6u4gpktf9hvr49fvv69fsnrn587vqeyj0ye

Ethereum Address: 0xd3786C8d3e3156219f3410432a9AC0F1970AC4Cc

Zcash (ZEC) Address: t1aMYjeXRs6mHzVs87fZ8yRiEwjhf9D69nN

Bitcoin Cash (BCH) Address: qq9l7u2z9qecul2er89m33vfjx8k0z28pcyzczc8gu

Binance Coin (BNB) Address: bnb1mm6hf3sn80p9pdrrxalscf9dgwqng4y6sqtk27

Monero (XMR) Address: 42ao68FPkhRYr41wRmEBSfKTQZsW8uY3cfCTsuUjpwSu9VmFkEYeaNRKpdZmeL8D6wUFryewswipTe43BFYpU43CJFk3eSE

Litecoin (LTC) Address: LNTyEAFD2X9b8hniwzGPqex57Kps3736w8

References and Further Reading

Central bank digital currencies: Foundational principles and core features | Bank for International Settlements

Shelling Out: The Origins of Money | Nick Szabo

Financial Freedom and Privacy in the Post-Cash World | Cato Institute

Money and Central Bank Digital Currency | Asian Development Bank

The Case for Electronic Cash | Coin Center

Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker | Atlantic Council

Hong Kong Protests Show Dangers of a Cashless Society | Reason

A Brief History of Money | Haseeb Qureshi

A Cashless Society- Benefits, Risks and Issues | Institute and Faculty of Actuaries

China’s Social Credit System: Speculation vs. Reality | The Diplomat

Withering Cash: Is Sweden ahead of the curve or just special?

Money creation in the modern economy | Bank of England

Facebook’s Diem White Paper | Diem Association

Please take a look at this paper: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40012-021-00327-6

Learned a lot from this! Thanks for contributing :)