Pandora Papers and Understanding the Economics behind Offshore Financial Markets

Whistleblowers, financial leaks, political revelations and “uncovering” scams are not very unusual these days. From Wikileaks releasing classified documents of political, diplomatic and historical importance in 2010 that exposed imperialist activities of the U.S. Army in Iraq and Afghanistan and Edward Snowden’s disclosures of highly classified information from the National Security Agency in 2013 to Luxembourg Leaks, Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Luanda Leaks, and now the Pandora Papers — the list is never-ending.

The Pandora Papers is receiving a significant level of media attention because it is the world’s largest-ever journalistic collaboration, involving more than 600 journalists from 150 media outlets in 117 countries. The wide range of disclosures make it one of the biggest revelations of financial secrets of wealthy individuals, world leaders, politicians, corporations, etc.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) reports in their article that the investigation is based on a leak of confidential records of 14 offshore service providers that give professional services to wealthy individuals and corporations, whereas in the case of the Panama Papers — the leaks were associated with a single entity Mossack Fonseca. The leaked documents associated with the Paradise Papers originated from the legal firm, Appleby. As the Indian Express notes:

The Panama and Paradise Papers dealt largely with offshore entities set up by individuals and corporates respectively. The Pandora Papers investigation shows how businesses have created a new normal after countries have been forced to tighten the screws on such offshore entities with rising concerns of money laundering, terrorism funding, and tax evasion.

The 2.94 terabytes of data that were leaked to ICIJ include more than 330 politicians and 130 Forbes billionaires, as well as celebrities, cricketers, fraudsters, drug dealers, royal family members and leaders of religious groups. The ICIJ has spent more than a year structuring, researching and analyzing the more than 11.9 million records in the Pandora Papers leak. The leaked documents were shared with media partners around the world in various formats.

So far, so good? Let’s understand some basic concepts involved in offshore financial economics.

What is a Tax Haven?

Liechtenstein, Switzerland, and Panama are some of the oldest tax havens in the contemporary world, dating back to the 1920s. Regardless of their existence for hundreds of years, we don’t have a generalized definition of a tax haven yet. Nevertheless, tax havens or offshore financial centres are low-tax jurisdictions that offer foreign businesses and wealthy individuals to set up businesses in the region with few regulatory requirements, mostly for tax avoidance purposes.

The benefits of tax havens originate from the inadequacy of chief forms of taxation such as income, corporate, real estate and gift taxes but most importantly, offshore financial centres provide various tax incentives such as very low effective tax rates on certain forms of foreign investment, making them very attractive for multinational corporations and wealthy individuals. They can be used legally and illegally to stash money earned abroad while avoiding taxes owed to domestic authorities.

The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) uses three key attributes below for identifying whether a jurisdiction is a tax haven. These are:

No or Only Nominal Taxes

Lack of Effective Exchange of Information

Lack of Transparency

Owing to their effective governance principles coupled with strong bank secrecy and legal entities where the information regarding offshore financial activities is difficult to extract from banks and financial institutions, these jurisdictions are also known as “secrecy jurisdictions.” Interestingly, a majority of tax havens deny being tax havens for businesses, but rather identify as “offshore financial centres.”

Where are these Tax Havens Located?

Tax havens are not concentrated in any single continent and are established all over the world. Not every tax haven is a country, but it could also be self-governing territories like the Cayman Islands, or specific regions within countries like the U.S. state of Delaware. Some of the popular tax haven jurisdictions are Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, British Virgin Islands, Hong Kong, Singapore, Panama, Malta, Bermuda, The Bahamas, Switzerland, Ireland, etc.

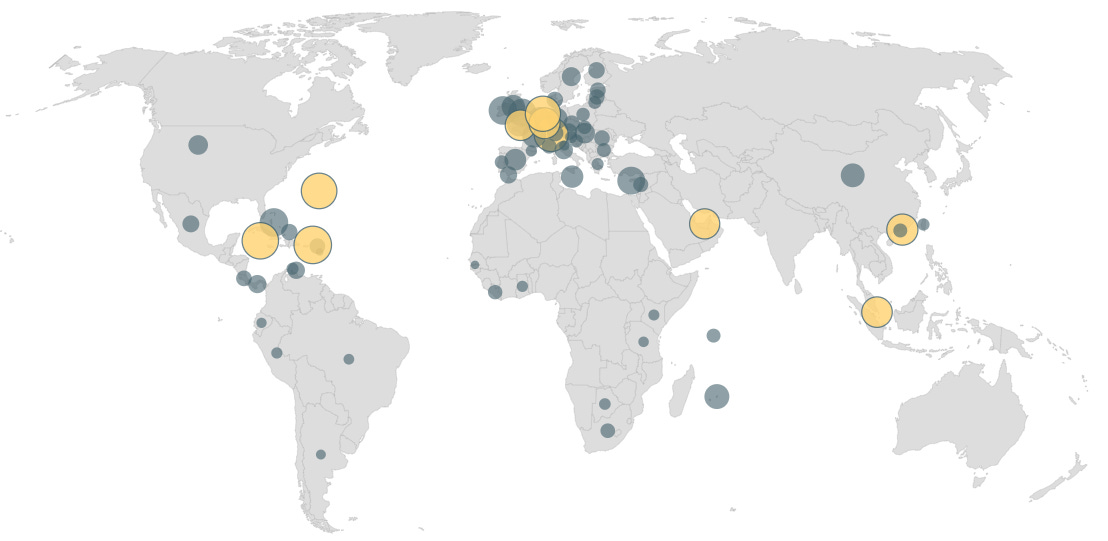

This map plots the tax jurisdictions all over the world, based on The Corporate Tax Haven Index, which is calculated by combining a jurisdiction’s Haven Score and Global Scale Weight to determine how much corporate financial activity it puts at risk of corporate tax abuse. The yellow circles represent the ten most significant Corporate Tax Havens.

It can also be observed that tax haven jurisdictions have better governance, are small in population size (mostly less than one million), are politically stable, rule of law, relatively less corrupted and democratic in nature. A 2006 research paper titled, “Which countries become tax haven” analyzed the effect of governance on the likelihood of becoming a tax haven jurisdiction, and it concluded that poorly governed countries are less likely to become tax-havens.

The reason why small, affluent, and better-governed territories are more likely to become a tax haven is that the returns to becoming a tax haven are greater for well-governed countries through higher foreign investment flows and the economic benefits that accompany them.

Over the last few years, especially after the Panama Papers revelations, financial activities in tax havens have come under severe international pressure and received harsh criticism — as a result of which, some tax havens, like Niue and Vanuatu, have cleaned up their act.

What is a Shell Company?

The ICIJ notes in their article that documents related to Pandora Papers reveal the creation of shell companies, foundations and trusts; their use to make investments and to move money between bank accounts; estate planning and other inheritance issues; and the avoidance of taxes through complex financial schemes. But what exactly are “shell companies"?

A shell company (also known as a shell corporation), is any legally structured entity that has no tangible assets or business operations. It exists only on paper, with no employees and no office. Wealthy businesses use shell companies to hide or misrepresent the assets of the shell company’s owner. Although, it might sound “illegal” but many shell companies operate in a legal grayscale area and wealthy businesses and individuals often use them to avoid paying taxes.

To give you an insight, the 11.5 million documents leaked during the Panama Papers exposed how the businesses and wealthy individuals used 214,888 offshore shell companies to avoid taxes in their home countries.

Shell companies registered in tax havens are used to hold assets such as luxury homes, intellectual property, real estate, aircraft, yachts, and investments in different financial assets. By doing so, it is possible for foreign corporations to hide their ownership of these assets from the rest of the world — allowing them to escape taxes in their home countries.

Why do Businesses Offshore their Finances to Tax Havens?

Well, basically for avoiding paying taxes. Various research studies have demonstrated that the overwhelming majority of multinational corporations use tools provided by tax havens for tax avoidance, and the scale of these activities has been growing. One of the most popular ways through which corporations use tax havens is by establishing offshore companies and shift profits to these subsidiaries located in tax havens.

Complex organizational structures enabled by the tax havens allow corporations to design their products in country A, manufacture in B, test in C, hold patents in D and assign marketing rights to a subsidiary in country E. Companies with the help of accounting firms then allocate costs to each country and shift profits across borders by exploiting gaps in tax rules — in order to take advantage of minimal tax rates in offshore financial centres and, thus, paying less or no taxes in the countries where the original profits are made.

Using similar “legal” tax avoidance arrangements, American corporations like Google, have been saving a lot on their taxes for several years. For example, Google shifted more than $75.4 billion (€63 billion) in profits out of Ireland using the controversial “double-Irish” tax arrangement in 2019. Google Ireland Holdings, an Irish subsidiary of Google, was incorporated in Ireland, but tax domiciled in Bermuda (another tax haven) — which allowed Google Ireland Holdings to escape corporation tax both in the Republic of Ireland and in the United States where its ultimate parent, Alphabet, is headquartered.

Tax avoidance strategies like base erosion and profit shifting have allowed businesses to reduce their tax burdens by a significant amount. For example, according to Oxfam International, the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies have avoided around $3.8 billion in taxes per year across 16 countries from 2013 to 2015.

Another reason why businesses find tax havens attractive is due to their remarkable level of secrecy enabled by the privacy laws in the jurisdictions they operate in. They release little to no information about the companies or trust incorporated there. The income tax department of any country can get the relevant information of beneficial owners by requesting an investigation agency or international tax authorities in tax havens — such exchange of information usually take months.

Wealthy families also use tax havens for inheritance or estate planning. In a nutshell, tax havens help large business families, corporations, wealthy individuals to consolidate their assets including financial investments, shareholding, and real estate properties. In some situations, tax havens can be used by people living in corrupt or politically unstable countries to protect their assets beyond the reach of oppressive governments or criminal rivals who may try to seize them.

Who Owns the Wealth in Tax Havens

Estimating the wealth that is stashed in tax havens and the beneficiaries of it can be useful to understand the negative implications of offshore financial centres on society. It can give us an approximate idea of true wealth inequality, especially in our globalized world, where measuring the wealth of rich households is getting increasingly hard. UC Berkeley’s economists led by Gabriel Zucman note in their research paper titled, “Who Owns the Wealth in Tax Havens?” that:

Global offshore wealth has increased considerably over the last four decades, as a growing number of offshore centres have entered the market for cross-border wealth management, and information technology and financial innovation have made it simpler to move funds overseas.

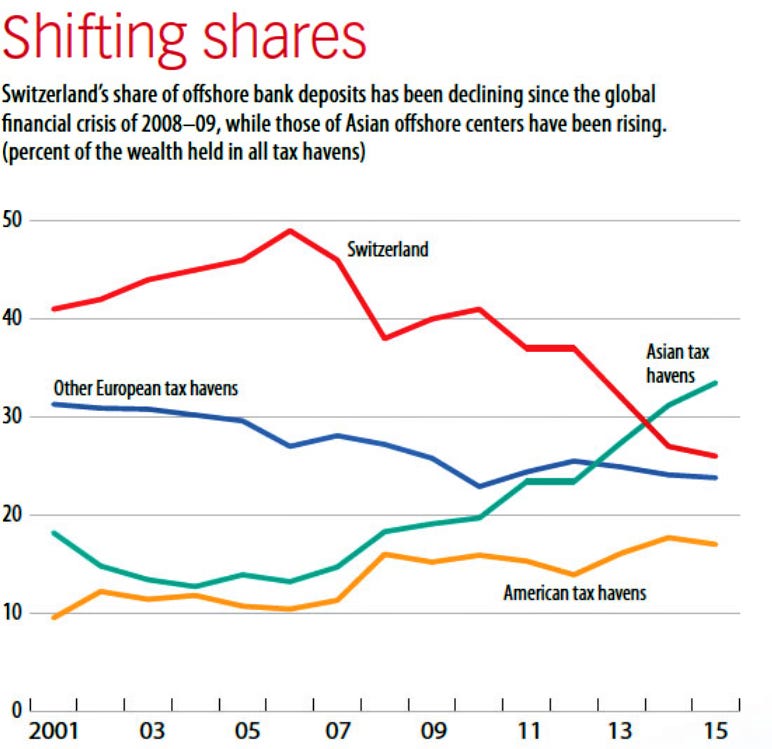

The researchers estimated that the total offshore wealth was about 10 per cent of world GDP in 2007 or 5.6 trillion dollars. They observe that half of the wealth was kept in Switzerland, the world’s premier offshore banking centre since the 1920s. However, in the last 15 years, the share of wealth stashed in Asian Offshore Centres such as Bahrain, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, etc. has been rising.

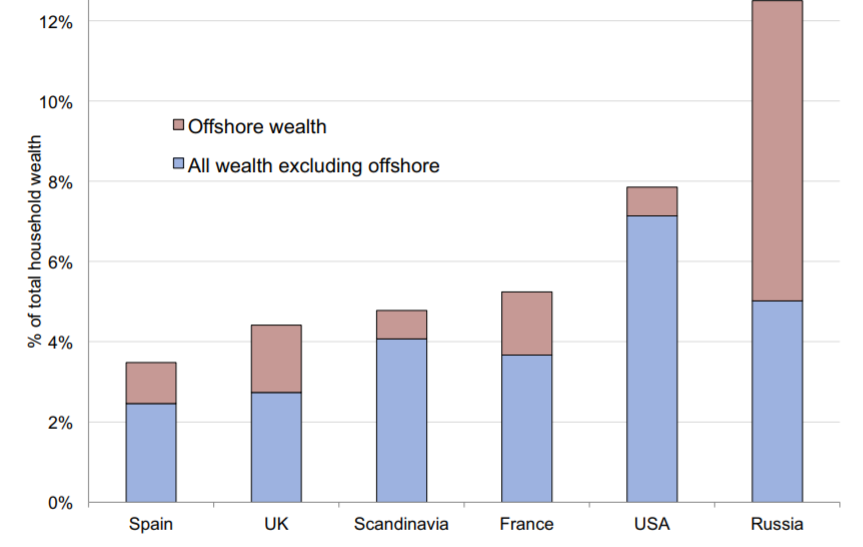

The following graph presents the share of wealth owned by the top 0.01% of society, including versus excluding offshore wealth. It shows that the share of wealth grows significantly after accounting for offshore assets. Accounting for offshore wealth held by corporations, wealthy families and individuals is helpful to give accurate estimations of wealth inequality, given the fact that corporations and others are most likely to channel their taxable money to tax havens for reducing their tax liabilities.

The researchers also conclude in their study that the distribution of offshore wealth is heavily skewed towards the rich, as the top 0.1% richest households own about 80% of it, and the top 0.01% about 50%. This is not surprising because banks, accounting firms and corporate service providers located in tax havens typically require their clients to have a minimum amount of financial assets to invest.

The Cost of Offshore Financial Centres

Tax avoidance, by both legal and illegal means, has a certain cost attached to it. Different research studies have come up with their own estimates of corporate tax revenues lost due to tax havens. The International Monetary Fund reports in their article that:

Tax havens collectively cost governments between $500 billion and $600 billion a year in lost corporate tax revenue, through legal and not-so-legal means. Of that lost revenue, low-income economies account for some $200 billion — a larger hit as a percentage of GDP than advanced economies and more than the $150 billion or so they receive each year in foreign development assistance. American Fortune 500 companies alone held an estimated $2.6 trillion offshore in 2017, though a small portion of that has been repatriated following US tax reforms in 2018.

As we have discussed earlier, corporations are not the sole beneficiary of tax havens. Wealthy families and individuals also find a rescue in tax havens for reducing their tax liabilities. Gabriel Zucman, Associate professor of economics at UC Berkeley, notes in his article titled “How Corporations and the Wealthy Avoid Taxes (and How to Stop Them)” that ultrawealthy families might have stashed $8.7 trillion or 11.5% of the entire world’s GDP in offshore financial centres.

James S. Henry, an investigative economist and a former Chief Economist at McKinsey & Co. puts his estimates at an astonishing total of up to $36 trillion. Another study by Mark B. Mansour of Tax Justice Network puts his estimation of loss of tax revenues at $427 billion. As he explains:

Of the $427 billion in tax lost each year globally to tax havens, the State of Tax Justice 2020 reports that $245 billion is directly lost to corporate tax abuse by multinational corporations and $182 billion to private tax evasion. Multinational corporations paid billions less in tax than they should have by shifting $1.38 trillion worth of profit out of the countries where they were generated and into tax havens, where corporate tax rates are extremely low or non-existent. Private tax evaders paid less tax than they should have by storing a total of over $10 trillion in financial assets offshore.

Lower-Income Countries are Disproportionately affected

According to The State of Tax Justice 2020 report, lower-income countries bear much greater consequences due to tax revenues lost to tax havens. Yes, it is indeed true that higher-income countries lose more tax ($382.7 billion) than lower-income countries ($45 billion) on an absolute amount basis, however, lower-income countries tax losses are proportionally larger when compared to the tax revenue they typically collect. As per their research, lower-income countries lose 5.8% of their collected tax revenue, whereas higher-income countries lose 2.5%.

This pattern seems to be driven by corporate tax avoidance by corporations. Additionally, the report highlights that lower-income countries, on average, are losing tax equivalent to nearly 52 per cent of their health budgets, while higher-income countries lose the equivalent of 8.4 per cent.

Who has been named in the Pandora Papers?

Okay, back to the discussion of Pandora Papers. The 2.94 terabytes of data leaked to International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) includes an unprecedented amount of information on beneficial owners of entities registered in various tax haven jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Hong Kong, Belize, Panama, South Dakota and other secrecy jurisdictions. The Pandora Papers do not only contain information on the offshore financial activities of wealthy individuals, celebrities, politicians, associates of dictators, corporations; but also include people who don’t represent a public interest such as small business owners, doctors, etc.

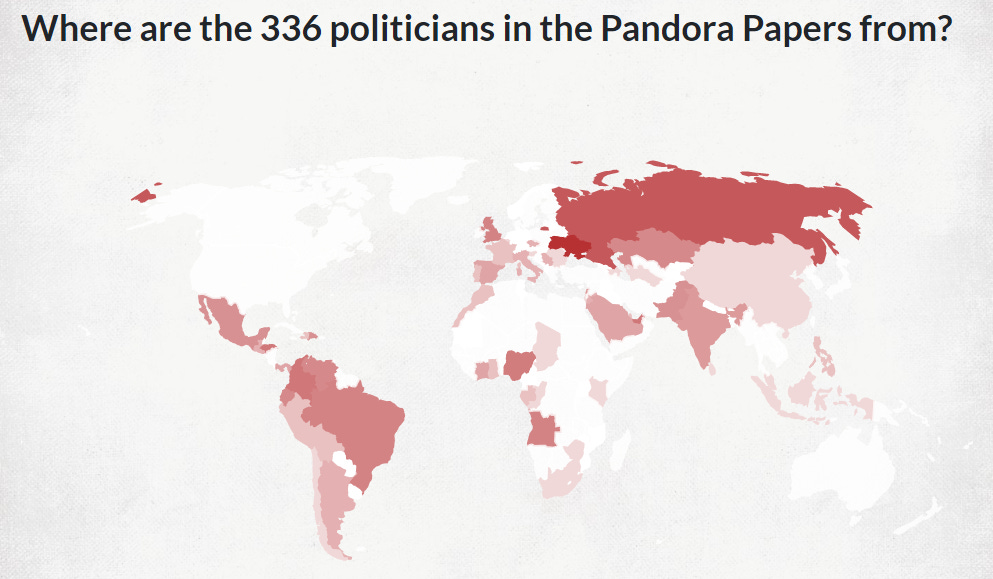

The leaked documents include more than 330 politicians from more than 90 countries and territories, including 35 current and former country leaders. The number of politicians and public officials associated with the Pandora Papers is more than twice the number of politicians whose offshore financial activities were exposed during the Panama Papers!

The reason why so many politicians are from Russia and Latin America is due to the location of the offshore service providers who leaked data to ICIJ. The majority of offshore service providers had Russian clients as one of their beneficiaries. For example, more than 40% of the companies that received services from Seychelles-based Alpha Consulting Group had one or more Russians as beneficial owners. Apart from Russia, clients from Latin American countries are among the largest beneficiary owners.

As far as it goes to the offshore financial activities of wealthy families and corporations from the United States, I am equally concerned as you are. As per the ICIJ, clients from different parts of the world with different needs select different providers and jurisdictions for their shell companies.

And the Pandora Papers do not cover all offshore service providers in tax haven jurisdictions, which could be a plausible reason why American companies are not a major beneficiary. Although, the Pandora Papers have identified 700 companies with beneficial owners connected to the U.S., I am not totally convinced with ICIJ’s explanation regarding the less representation of US corporations and individuals in the Pandora Papers.

I mean, it is quite ironical how the ICIJ claims their investigation is the “world’s largest-ever journalistic collaboration” but at the same time they maintain that their investigation do not cover all tax havens and hence, rationalize away the zero representation of US politicians, public officials and multinational corporations that have a prolonged history of tax evasion and tax avoidance. After all, how do we check the selective biased-ness of these investigative reports that usually have soft approach towards the United States? I am extremely curious to know this!

Suggestions to Reduce the Influence of Tax Havens

A majority of people consider that any solution proposed to tackle the tax avoidance through offshore financial activities would be ineffective, given the wealthy corporatist class would still find loopholes to reduce their tax liabilities with the help of big accounting and legal firms. But that doesn’t mean the world of financial secrecy enabled by the tax havens cannot be eliminated at all, I believe with the proper alignment of incentives, and a strong political will could lead us in the right direction.

This is especially important in the present times, as the wealth gap between the rich and the poor is rapidly widening, corporations have not been paying a good chunk of taxes that they owe, the middle-class and poor bear the greater portion of taxation — either through taxation (direct and indirect) or via inflation. I mean, it is quite unfair the way average individuals are penalized by tax authorities for failing to file tax returns and then there are MNCs, with all their political, legal, accountancy and economic privileges avoid taxes through “legal” and “strategic tax governance” means.

Gabriel Zucman is one of the world’s leading experts on tax havens and the author of the popular book “The Hidden Wealth of Nations”, in which he has proposed many solutions that could possibly reform the cross-border corporate tax system. I would encourage you to read Zucman’s book if you are truly curious about this topic — although we will discuss some solutions here.

Zucman advocates for changing the current territorial corporate tax system, under which multinational corporations are taxed in the countries where “they claim” to have earned their profits, to an alternative tax system named “formulary apportionment” system — where profits of a multinational corporation would be determined using a formula based on some combination of its sales, assets, and payroll in each jurisdiction.

Secondly, Zucman suggests creating a comprehensive international financial registry that would record the true individual owners of real estate and financial securities, including equities, bonds and mutual fund shares. Such a system might sound dystopian, but he claims that many countries already have such registries — and with the assistance of financial expertise, countries could join together to effectively create one global registry. But again, such policies require tremendous political will.

On the other hand, public interest organizations like Tax Justice Network proposes to introduce a global unitary corporate tax system, under which corporate profits would be identified at the global level, not the national level. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), recently said that 136 jurisdictions have agreed upon the global minimum corporate tax rate of 15% to be imposed by 2023. Measures like these “might” prevent multinational corporations from underreporting their profits at the domestic levels — although I am not sure how it will fix the other tax avoidance loopholes.

Oxfam, an independent charitable organization, calls on governments to ensure all multinational companies publish their financial reports for every country where they operate — in a transparent manner. Additionally, they also put forward a proposal to strengthen “global tax governance by creating a global tax body where all countries can work together on an equal footing to ensure the tax system works for everyone.”

Oxfam claims such a system would improve global tax governance, eliminate tax competitions between countries, and reduce corporate tax avoidance to a considerable extent.

Of course, this list of proposals to limit tax avoidance by corporations and wealthy families is not exhaustive, but you can check the policy papers of Oxfam, Tax Justice Network and OECD for more information. Having said that, I am personally not sure about the effective implementation of these policies, because unravelling the twisted layers of financial secrecy would require an extreme level of political determination, especially from developed countries.

I am an independent researcher and my newsletter completely relies upon your support, so if you find my articles helpful and informative, then please subscribe to my periodic newsletter, share this article with your friends and tell them to subscribe too! Thank you so much :)

References

https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/about-pandora-papers-leak-dataset/

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/09/offshore-tax-havens-and-inequality-picture.htm

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/why-do-the-pandora-papers-matter-7550033/

https://theintercept.com/2021/10/05/pandora-papers-offshore-tax-havens/

https://gabriel-zucman.eu/how-corporations-avoid-taxes/?utm_source=pocket_mylist

https://taxjustice.net/reports/the-state-of-tax-justice-2020/

https://www.zdnet.com/article/how-google-shifts-profits-to-bermuda-to-shrink-taxes-by-billion/

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/09/tackling-global-tax-havens-shaxon.htm

https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/drug-companies-cheating-countries-out-billions-tax-revenues