The Panic of 1825 and How it Challenged the Credibility of Classical Economics

How distinctively Marxist and Austrian schools of economic thought offer an explanation to the financial panics of the 19th century.

In 1776, a Scottish philosopher named Adam Smith who is often considered as the father of Modern Economics published his popular book “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” in which he argued for free trade, minimal government intervention, market-driven prices, the invisible hand of the market and so on. Adam Smith’s work was followed by the theories of other classical economists such as David Ricardo, Jean-Baptiste Say, etc. where they asserted the idea of “Market Knows Best.”

Adam Smith maintained that the “free market” would tend towards economic equilibrium through the wage-price mechanism. He asserted that the market forces of demand and supply will adjust themselves - leading to a stable economic equilibrium. On the other hand, Jean-Baptiste Say claimed that the supply of goods creates its own demand. Say refutes the case of overproduction in an economy and asserts for general equilibrium.

To summarise what Classical economists believed in, they claimed that there will always be full employment in the economy – full employment not only of labour but also of other major resources such as land, capital, and other factors of production. They postulated that any deviation from full employment will be corrected by the changes in the wages as they believed that in the capitalist system, wages as also prices (including interest rates) are flexible and not rigid but in many cases but in reality, wages tend to be “sticky” in nature and are not as flexible as what classical economists believed in. The early classical economists’ belief in market adjusting forces leading to an economic equilibrium necessarily means that they ignored the occurrence of any economic booms and busts in unfettered markets. They had either overlooked short-term booms and busts or had attributed them to external events such as wars, pandemics, medical emergencies, and natural calamities.

A Swiss economist Jean Charles Sismondi was one of the first thinkers who challenged the classical “orthodoxy” of “Market Knows Best” and general equilibrium in an economy. Sismondi thought a sort of equilibrium would be reached but only after a “frightful amount of suffering.” Sismondi was the first economist who formally identified the cause of business cycles in an unfettered market. In his 1819 book, “Nouveaux Principes d’econmie politique” (New Principles of Political Economy) Sismondi showed that short-term economic movements, causing business cycles as overproduction and underconsumption and blamed growing inequality during booms.

Okay, so one would be wondering why am I emphasizing these historical debates when the post is titled around "The Panic of 1825". It’s primarily because the Panic of 1825 was the first documented economic crisis, occurring in peacetime and caused solely by internal economic events unlike external factors such as wars, pandemics, etc. It is argued that economic crises like the Panic of 1825 and the Panic of 1837 challenge the theoretical basis of classical economics.

The Panic of 1825

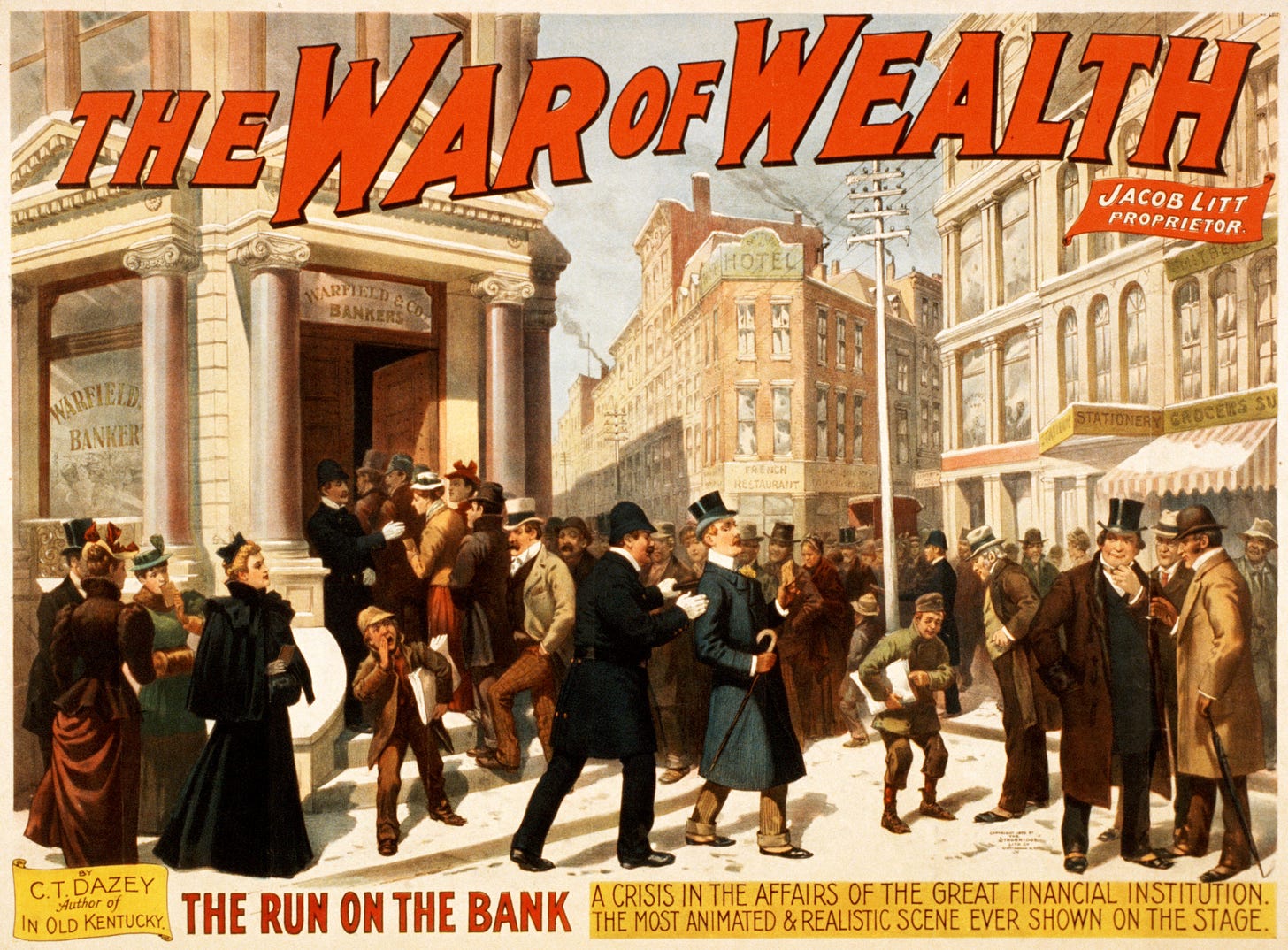

The Panic of 1825 was a stock market crash and was mainly centered in Britain - arising in part out of speculative investments in Latin America, including an imaginary country: Poyais. It was severely felt in Britain, where it led to the closure of six London and 60 country banks in England. More than 10% of England’s country banks went bankrupt, runs occurred on many London Banks - causing several major banks to temporarily stop payment and others to fold entirely. The real economic activity declined dramatically.

The crisis was channelized in other parts of Europe, Latin America, and the United States. To put it in perspective, John Turner - who has extensively studied the banking history of England puts only the panic of 1825 on par with the Great Recession of 2007-08 in terms of financial distress and output costs.

Factors that led to the crisis

A number of historical developments such as the Napoleonic war, many Latin American countries gaining independence, vague monetary policies of the Bank of England, etc were at play that led to the Panic of 1825. Considering the limited understanding of the economics of some readers, I might not cover every cause that led to the crisis but I will cover the most important ones.

1. The Napoleonic Wars and Peace

After early 1793, Britain remained heavily involved in far-reaching Napoleonic Wars and the French Revolution. This was a large period of conflict that required a huge increase in government spending. Britain’s massive war expenditure was financed by the issuing debts - a strategy of financing wars that had been prevailing since the early 18th century. The government even imposed the country’s first progressive income tax as a temporary measure to finance its expenditure.

2. Expansionary Monetary Policy

As obvious it seems, Britain followed the expansionary monetary policy to survive the massive war expenditure. In 1797, Britain passed the Bank Restriction Act 1797, allowing them to suspend the convertibility of gold into banknotes, enabling it to issue additional un-backed paper currency. Throughout the period, expansionary monetary policy and easy credit also caused Britain's currency to depreciate and its exchange rate to fall. This era of easy credit led to speculative investments and bad loans, leading to an economic bubble. This economic bubble resulted in a crash in 1810, resulting in many business failures.

Following the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, the Bank of England began adopting the deflationary or contractionary monetary policies to restore the exchange rate levels and gold convertibility at the pre-1797 suspension parity - leading to a successful resumption in 1821. After 1821, the country witnessed a period of expansion characterized by both an investment and export boom.

3. Stock Market Bubble

During this period, many Latin American countries had gained independence which stimulated a boom in British exports, and meanwhile, due to rapid industrialisation, various infrastructure projects fuelled investment expenditures. All these factors coupled with the credit expansion by the Bank of England led to a massive stock market boom. The mania was further fuelled when the Country banks started issuing additional notes to finance the economic activity and stock market speculation. The banks did not realise that they were making risky loans and eventually, the stock market boom became a bubble as investors bid up the prices of real and imaginary stocks and as always happens, the bubble burst - leading to the Panic of 1825.

Challenging the Classical Economics

By now, one would be wondering, how the economic crisis of 1825 is linked to the major tenets of classical economics. As discussed above, David Ricardo is one of the most influential classical economists of all time. The Panic of 1825 and the panic of 1837 particularly challenged the credibility of the Ricardian theory of world trade and comparative advantage.

The Panics of 1825 and 1837 were both preceded by major external drains of gold. The Bank of England took measures to stop the gold drains which they did it successfully but it was followed by the financial panic. But this was exactly what was not supposed to happen according to the Ricardian theory of world trade and comparative advantage. According to the Ricardian theory, any external gold drain signalled that the prices were too high in Britain compared to its trading partners but such a situation would not sustain for long as in such situations, prices and wages will decline in order to bring back the trade and balance of payments on an equilibrium level.

The process of wage and price changes to correct the gold supply of Britain would develop gradually and according to the theory, this mechanism would ensure that the world’s gold reserves would be distributed in exactly the proportions that were necessary to allow the law of comparative advantage to operate to the mutual benefit of all trading nations regardless of their degree of development. There was no scope to the economic crises unless it would cause due to natural calamities, wars and external shocks. The factors which were missing from the theory happened in practice both in 1825 and 1837.

The reform proposed by the ‘Currency School’

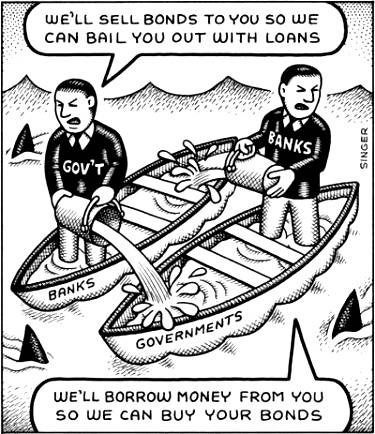

Supporters of Ricardian comparative advantage theory (mainly belonged to the British Currency School of 19th Century) realised that things were going wrong and they knew how the situation could be corrected. They believed that the financial panics were not caused by the flaws in Ricardian theory but rather by bad banking practices - which could be prevented in the future by proper legislation. The reform proposed by the Ricardian theory supporters resulted in the Bank Act of 1844.

The new legislation proposed that the quantity of banknotes would be tied to the inflow and outflow of gold. With the implementation of the reform, the Currency school asserted that the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage would begin to work which would offset any deviations from the balance of trade and payments. The supporters predicted that the “general gluts” of commodities that followed the panics of 1825 and 1837 would not recur in the future.

But things did not go as they were planned. Three years after the Bank Act was implemented, Britain witnessed yet another financial panic in 1847. The Bank Act had to be suspended in an attempt to stop the economic crisis. A decade later in 1857, during yet another financial crisis, the Bank Act had to be suspended in order to quell the panic. Interestingly, the Bank Act had to be suspended once again during the Panic of 1866. Crisis after Crisis, why the Bank Act proposed by the Classical economics supporters was not working? One possible explanation could be that prices did not react the way theory assumed they would.

Marxist Perspective on the Financial Panics

The financial panics of the 19th century had a significant impact not only on classical economics but also led to the development of Marxist literature. In fact, many people started noticing the frequency of crisis. Friedrich Engels was inspired by the Panic of 1837 as he practically witnessed the exploitative and devasting conditions of the British working class while he was employed in his family’s mercantile firm. He observed the consistency of these crises. He described it as "they (economic crises) reappear as regularly as comets” and he criticised the political economists belonging to the Classical school of economic thought for their willful ignorance of financial crises that were prevailing regularly in the 19th century. Even for Engels, the crises persisted because the prices did not communicate as expected by the Classical theory. Engels strongly believed that the periodic reoccurrence and increasing intensity of economic crises will eventually lead the society towards an economic and political revolution that would dismantle the system of private property.

In the late 1850s and 1860s, Karl Marx joined Engels and pushed his criticism even further. In “Ricardo’s Denial of General Overproduction. Possibility of a Crisis Inherent in the Inner Contradictions of Commodity and Money” - 8th chapter of the book The Marx-Engels Reader the Marx’s view is quoted as -

“So far as crises are concerned, all those writers who describe the real movement of prices, or all experts, who write in the actual situation of a crisis, have been right in ignoring the allegedly theoretical twaddle and in contenting themselves with the idea that what may be true in abstract theory—namely, that no gluts of the market and so forth are possible—is, nevertheless, wrong in practice. The constant recurrence of crises has in fact reduced the rigmarole of Say and others to a phraseology which is now only used in times of prosperity but is cast aside in times of crises.”

Marx further attacks by saying “Instead of investigating the nature of theconflicting elements which errupt in the catastrophe, the apologists content themselves with denying the catastrophe itself and insisting, in the face of their regular and periodic recurrence, that if production were carried on according to the textbooks, crises would never occur. Thus the apologetics consist in the falsification of the simplest economic relations, and particularly in clinging to the concept of unity in the face of contradiction.”

Following the work of Karl Marx and Engels, the methodological approach of economics had started changing and by the late 1860s, thinkers belonging to the classical school of economics started recognising the occurrence of business cycles in an economy by analysing various numerical evidence. For instance, in 1862, Clément Juglar, a French physician and economist, published the first book-length argument about the regular recurrence of crises. His analysis proposed a seven to ten years time period between crises. In 1867, John Mills in his groundbreaking article “Credit Cycles and the Origin of Commercial Panics” explained the occurrence of business cycles as a part of a “credit cycle” that was caused by the psychology of businessmen. Thus for many reasons, many economic theorists started hunting for economic crises as a part of their analysis which led them to look backwards to the financial panics of 1825, 1837, 1847, 1857, 1866 and 1878.

By the 20th century, financial panics might have lost their place in economics but for economic historians, multiple events of financial panics of the 19th century reveal how the methodological and analytical approach to economic theory evolved gradually and how the orthodoxy of the classical school of economics was challenged by different schools of thoughts.

The Austrian School’s Perspective

The analysis presented in this article might appear constructive and outright, but this examination is not complete unless we take into account the perspective of the Austrian school of economics. The Austrian school of economics is yet another economic school of thought which was founded in the late 19th century by Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and Friedrich Wieser. Supporters of this school are in favour of free markets. private property, market prices which acts as an information signal for market participants, subjective value theory, gold-backed currency, free-market banking, minimal-to-no government intervention and praxeological analysis of economic theory.

Austrian supporters might sound similar to classical economists or currency school supporters but they differed widely in their methodological approaches to economic theory and economic crises. Austrians acknowledge the importance of interest rates in coordinating intertemporal consumption and investment decisions and thus, they find the intervention by central banks which often influence changes in monetary aggregates very troubling. They emphasize that the credit expansions by central banks in order to “stimulate economic activity” do create a space for bad loans and “malinvestment” - leading to artificial economic booms in an economy. They emphasise that these credit induced economic bubbles driven by wrong interest rate signals would not last for long and will eventually burst, paving way to economic recessions.

Just like other economists, Austrian economists have thoroughly analysed the financial panics of the 19th century but their explanation of the crises differ from that of Marxists and Currency School supporters. Jesus Huerta de Soto’s 1998 book titled “Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles” have briefly summarised the explanation of the financial crises from an Austrian point of view. The author argues that almost every financial panics of the 19th century was preceded by an expansion of credit and of the money supply which gave a space for “malinvestment”, speculation and bad loans. The result would always be an artificial economic bubble that would eventually burst - leading to financial panics and economic recessions. Murray Rothbard, yet another famous Austrian economist provides a similar analysis in his book “The Panic of 1819”. Interested readers can refer to these textbooks for further conceptual understanding.

The financial panics of the 19th century were crucial to the development of modern economics as they paved the way for the growth of different schools of economic thought. Despite my disagreements on some economic issues with Austrians, I tend to agree with their explanation of how economic booms fuelled by easy credit lead to economic recessions but having said that, I do not entirely reject the Marxists’ criticism of Ricardian theory and their differences of opinions with the idealistic approach of the classical school of economics.

References and Further Reading:

Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles by Jesus Huerta de Soto.

“Ricardo’s Theories Challenged by the Crises of 1825 and 1837” by a blog named “A Critique of Crisis Theory” - which often talks about economic issues from a Marxist point of view.

The Many Panics of 1837 by Jessica Lepler.

Excerpts from “Theory of Surplus Value” by Karl Marx.

Murray Rothbard’s book “The Panic of 1819”.

A research paper titled “Marxism, Crisis Theory and the Crisis of the Early 21st Century”.

If you are impressed with my articles then please consider sharing them with your friends. Please support my newsletter by subscribing and encouraging others to subscribe. A good response will definitely encourage me to be better and provide motivation for writing such articles in future.